Diptych: Falling Planes

2016 – 2017

This video diptych is based on archival footage from the World War One period. The black and white footage is grainy and silent. I enlarged the images and slowed the frame rate to evoke a sense of immediacy and poignancy as the viewer watches a distant smudge representing a man in an airplane falling to his death. The video is looped so there is a slow motion, never–ending fall that has a dream–like character. The two projections are designed to be shown on opposite walls at as large a size as the space allows in order to enhance the sense of immediacy and viewer engagement. The use of airplanes in the imagery links with my theme of questioning technology’s role in culture. Aviation was in its infancy when war broke out in 1914 and airplanes represented the high-tech of the era. Despite resistance on the part of some in the military, airplanes became a key component of a new approach to warfare that had literally expanded upwards into a new dimension. Soon, dominance of the air above the battlefield became critical. Aviation technology developed rapidly with lavish funding and the dread of losing the war. Airplanes were made stronger, faster, and more deadly. However, as Arthur Gould Lee documented in his memoir "No Parachute", the development of safety technology did not keep pace with the development of the technology of destruction. Early in the war, only the crews of stationary, gas–filled balloons had parachutes. And late in the war, the Germans were the only air force to issue parachutes to airplane pilots. The potential for a fiery crash was the dread of every aviator. Although some, like the Canadian Second Lieutenant A. A. McLeod VC, survived such an event, others carried a pistol with them in order to commit suicide rather than burn to death.

Falling: The Past Is Always Present

Reflections on the Great War

1914–1918

MFA Thesis Exhibition, August 2017

War has been the subject matter I’ve been exploring over my time in the University of Ottawa MFA program. The immediate impetus for this was the one hundredth anniversary of World War One, the so-called Great War, also known as ‘The War to End All Wars.’ The irony of that last label is apparent when we look back on a century littered with the corpses of the millions who died in conflicts after the Armistice of 1918. But irony is a quality that applies to all wars, according to literary and cultural critic Paul Fussell. A veteran of the Second World War, in which he was badly wounded, Fussell wrote “Every war is ironic because every war is worse than expected. Every war constitutes an irony of situation because its means are so melodramatically disproportionate to its presumed ends. In the Great War eight million people were destroyed because two persons, Archduke Francis Ferdinand and his Consort, had been shot. […] But the Great War was more ironic than any before or since. It was a hideous embarrassment to the prevailing Meliorist myth which had dominated the public consciousness for a century. It reversed the Idea of Progress.”

The “Meliorist myth” and the “Idea of Progress” are apt summaries of what I think of as blind faith in technological progress. In this context, the imagery of The Fall relates to loss of faith in the myth of progress and in the entire project of Modernity. It’s a fall from the heights of irrational enthusiasm into the depths of a rather bloody and dangerous reality. I’ve incorporated the imagery of The Fall into three works: Diptych of Falling Planes, a video diptych of World War One biplanes engaged in combat, with one spiralling down, smoking; Falling Bodies, a ‘holographic’ projection of animated images of falling bodies; and Fallen Figure, a video projection of a 1916 photograph of the indentation made in the ground by the body of a fallen Zeppelin crewman.

Diptych: Falling Planes Part 1

Video loop

Diptych: Falling Planes Part 2

Video loop

Falling Bodies

2016 – 2017

Icarus is one of the images I’ve included in the Falling Bodies animation presented as a ‘holographic’ projection. I put ‘holographic’ in inverted commas, as that’s a term of art rather than science. Whereas lasers are used in the creation of actual holograms, the World Wide Web, YouTube in particular, is rife with reference to holograms that are actually a miniaturized version of the Pepper’s Ghost illusion. This illusion dates to the mid-nineteenth century and has been widely used theatrically to produce the impression of a three–dimensional object or body using a light source and a transparent projection surface at 45º to the light source. The image appears to float behind the transparent surface. In Falling Bodies, the looping animation plays on a tablet computer sitting horizontally on a surface. An inverted truncated pyramid made from transparent material sits atop the tablet computer and reflects the animated images, making them appear to float in the middle of the pyramid. Each of the five images in the sequence is a silhouette appropriated from work by other artists and animated to twist and spiral away from the viewer until the image disappears in the far distance. The viewer thus has a god-like view of the events as these small, nearly insignificant, black and white figures recede into nothingness. The first image is from a painting in the Canadian War Museum’s collection called The Fall. It depicts a German World War One pilot jumping from his burning airplane. Dating from 1918, it was remarkable for its digression from the narrative of heroism conventionally associated with aviation of the period. Knights of the Air didn’t abandon ship! The next three images were made in the twenty-first century relative to the destruction of the World Trade Centre in 2001. One is of Eric Fischl’s Tumbling Woman sculpture while the other two are extracted from Carolee Schneemann’s Terminal Velocity, which itself is composed of news images of people jumping/falling from the burning buildings. Lastly comes Icarus, as created by Henri Matisse in his book "Jazz" in 1947. The intention was to link an image specific from World War One with others from a more recent aviation trauma to make the point that The Fall continues today, the past is always present. The image of Icarus helps to add a mythic and timeless element while pointing to Modernist art as a component of the problematic of Modernity.

Falling Bodies

Animation loop

Fallen Figure

2016 – 2017

Fallen Figure, the video projection of the photo of the fallen Zeppelin crewman, extends the imagery of The Fall to its logical conclusion. Whether precipitated by a jump or otherwise, after The Fall comes the landing. This photo was taken at the crash site of German Zeppelin L31, which was shot down over London, England, in October 1916. The black and white image is projected on the floor at life size. It shows the deep indentation made in the grass and turf by the body of one of the Zeppelin crew when he fell or jumped from his burning airship. The indentation is distinctly in the shape of a human body, though slightly distorted. Although Zeppelins did no major damage to the British war infrastructure, they terrified the population. The airships were so large and flew so high they were almost immune from attack. The downing of L31 was a rare event and it attracted a huge crowd of spectators who reportedly paid a shilling each to view the wreck. It may be apocryphal, but the indentation photographed was said to have been made by the body of Kapitanleutnant Heinrich Mathy, commander of the airship. Zeppelins were held aloft by immense bags of hydrogen gas, making them lighter-than-air. Unfortunately, hydrogen is highly flammable, which meant that a fiery plunge to earth awaited a crew if they were successfully attacked. Such was the fate of L31. Whether the photo represents the aftermath of a jump or a fall, the end result was the same. The image bears mute and rather sanitized witness to the dangers of aviation technology and the consequences of conflict.

Fallen Figure

Projected still image

Triptych: War Songs

2016 – 2017

Using a strategy of ironic juxtaposition, the videos in this triptych show jarring images of victims of the war to a sound track of morale-boosting popular songs from the 1914–1918 period. The first song is Pack Up Your Troubles, recorded circa 1915, which I paired with archival still images of soldiers with horrendous facial wounds. The second is It’s A Long Way To Tipperary, which became an international hit in 1914 for the Irish tenor John McCormack. I added archival film footage of soldiers suffering from the new and mysterious condition called Shell Shock in World War One. The third element of the triptych pairs a recent recording of a song from 1917-1918 with a photograph of the body of an American pilot, Quentin Roosevelt, lying beside his crashed airplane. The Germans used this photograph for propaganda purposes since Roosevelt was the youngest son of the former president Theodore Roosevelt. The song, called The Young Aviator, was quoted in several of the pilot’s memoirs that I read, and is an example of the mordant humour used to dispel tension and anxiety in the aftermath of aerial combat.

The content of these videos was inspired by Ernst Friedrich’s anti-war book War Against War! from 1924.

Triptych: War Songs – Pack Up Your Troubles ...

Video loop 2:57

Triptych: War Songs – It’s A Long Way To Tipperary

Video loop 3:26

Triptych: War Songs – The Young Aviator

Video loop 00:44

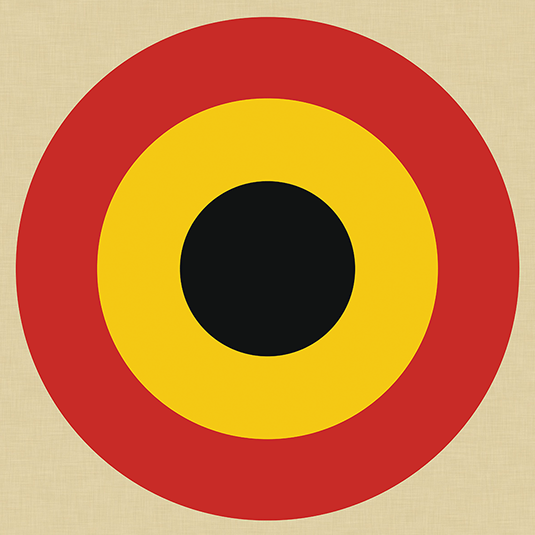

Aircraft Identification Markings

2016 – 2017

I considered the theme of Nationalism by means of large banners printed with aircraft identification markings used by the belligerent nations. These were presented in such as way as to allude to mass rallies by nationalist movements in the post-war years, like the Nazi rallies as Nuremberg. The shape of the emblems also called to mind images from the canon of Modernist art such as Malevich’s Black Square, 1913, Marsden Hartley’s Portrait of a German Officer, 1914, and the target paintings of Jasper Johns. These, plus the inclusion of Matisse’s Icarus in the Falling Bodies animation, alluded to the war as an event that was both a logical outcome of the project of Modernity as well as a stimulus for a backlash on the part of some of the Modernist avant-garde. I say some of the avant-garde because groups like the Italian Futurists and English Vorticists openly welcomed warfare as a way to enhance the experience of living and also to purge society of decadence. Others, like the Dadaists and Surrealists, retreated from modernity’s emphasis on the rational in reaction to such calamities as the war. They were attuned to how, in Fussell’s words, “ … It reversed the Idea of Progress.”

Aircraft Identification Markings

Sample Drawings